|

|

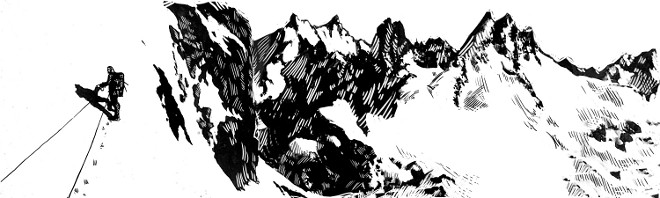

As I pulled onto the summit, the western horizon opened before me. To the northwest, 60 miles away, Mount Baker stood in icy silence. A hundred miles southwest was the ghostly bulk of Mount Rainier.

Just a few days earlier, warm weather and heavy rain had pounded the North Cascades. Wet snow had frozen to every inch of Bonanza’s summit pyramid, offering us a safe and relatively easy ice climb. We were blessed with clear skies and calm wind, but as we stood on the summit, clouds from the next storm were already spreading across the sky. Like burglars, we had sneaked into the Cascades through a window of fine weather, and we knew we’d better escape before that window closed again. No Place to LingerThe North Cascades are notoriously inhospitable in winter. The greatest seasonal snowfall on earth — 1140 inches — was recorded at Mount Baker Ski Area in 1998-99. A typical Cascade winter brings not only deep snow, but also periods of heavy rain. For the winter traveler, these conditions mean exhausting travel, danger from hypothermia, and serious avalanche risk. For centuries, Native Americans crisscrossed the Cascades during the snow-free months of the year. Mid-winter ventures were probably rare, but spring forays have been well documented. In 1870, Daniel C. Linsley, a scout for the Northern Pacific Railroad, crossed the North Cascades near Glacier Peak in the company of Skagit Indians. Encountering deep snow at Kaiwhat Pass, Linsley’s guides introduced him to the art of glissading — sliding down the mountain on their butts. Linsley wrote that it was “not the most dignified mode of traveling known, but it was an eminently successful one in my case.” Deterred by the rugged terrain that Linsley found, Northern Pacific chose a route much farther south, over Stampede Pass in the Central Cascades. In 1887, their competitor, the Great Northern Railroad, commissioned Albert B. Rogers to make another attempt to find a pass through the North Cascades. Five years earlier Rogers had discovered the pass in the Selkirks of British Columbia that now bears his name, yet he failed in his Cascade quest. Rogers reported to the railroad that avalanches on the western slope of the Cascades were “much worse than any in the Selkirks.”

In 1890, however, John F. Stevens discovered a previously unknown pass that was suitable for a railroad crossing. The Great Northern line was completed over Stevens Pass in 1893. Initially, white Americans ventured into the North Cascades in winter for two reasons — fur trapping and mineral prospecting. Trappers were attracted by fox, marten, otter, and mink. On the east side of the North Cascades, men like A.L. Cool, Gordon Stuart, and Hugh Courtney trapped in the valleys above Lake Chelan in winter in the early 1900s. They were preceded by a generation of men whose names are forgotten, trappers who traded with the Hudson’s Bay Company in the mid-1800s. On the west side of the crest, Gaspar Petta trapped on snowshoes at the foot of the Picket Range (near Jasper Pass) from 1912 to 1956. John Dayo wintered for a few years at Rock Cabin near Mount Logan in the 1920s. Many families in the Skagit Valley depended on trapping for their living. They would run trap lines back into the mountains and build small cabins for overnight shelter. The same was true on the east side of the range. Prospectors roamed the mountains in summer searching for gold and silver. Once a strike was made, they dug in, and in some cases worked throughout the year. The Silver Creek mining district, about 10 miles northeast of Index, is the oldest mining area in the western Cascades of Washington, dating back to 1871. Prospectors starting out from Silver Creek discovered what would become the Monte Cristo district in a nearby valley. By the early 1890s, year-round mining camps were established at both Silver Creek and Monte Cristo. The first records of snowshoeing and skiing in the Cascades emerged from these camps. Prospectors had a powerful incentive to venture into the mountains in winter. According to U.S. mining law, claims that hadn’t been properly worked during the previous year could be relocated (claimed by others) on New Year’s Day. The practice was described in the Monte Cristo newspaper in January 1896: “All day on Tuesday, December 31st, men could be seen, well provided with snowshoes, ski, provision, flat bottles, alpenstocks and hatchets, taking their devious way up the hillsides south, north and east, nearly all of whom remained out overnight, in order to place their stakes on coveted ground exactly at midnight.”

Winter work in the mines subjected the men to privation and avalanche danger. Following the decline of Monte Cristo around 1920, year-round mining operations sprang up at Trinity, along the Chiwawa River above Lake Wenatchee, and the Azurite Mine, over the Cascade divide northwest of the Methow River. Both locations were accessible in winter only by dog sled, snowshoe, or ski. January 1935 was a terrible month for avalanches, with four deaths in three separate incidents in the Azurite country. Ray Walters described the experience in a letter to his wife, Jessie. Following a bitter cold spell, he wrote: “It turned warm and started to snow. I never saw anything like it — seven feet fell in two days. It then started to rain and poured down for three days. The old snow was packed hard and conditions were just right for snow slides. They started at once and hell was popping for five days. There was hardly a five-minute interval that you couldn’t see a slide running in the daytime or hear one roar at night. Some of the big ones filled the air with snow so you could hardly see. Little slides ran between and against the camp building and bigger ones stopped just a few feet above them. [...] Our bull cook (Charlie Graves) stepped out of the kitchen to get a pail of water and was buried in a slide. The cook did not miss him for about ten minutes and after he gave the alarm it took forty-five minutes of digging by the whole crew to find him and get him out. [...] Some of the boys got panicky and went to the [mine] tunnel and root house to sleep.” Holden, the starting point for our winter climb of Bonanza Peak in 1979, was a major year-round copper mine from 1938 until 1957. But the town was not isolated like the Azurite Mine, and avalanches were less of a problem. After the mine closed Holden became a Lutheran church camp, which it remains to this day.

This essay was written for the book, Snow & Spire: Flights to Winter in the North Cascade Range, by John Scurlock, released by Wolverine Publishing in 2011. Artwork by Donald A. Smith. |

The Alpenglow Gallery